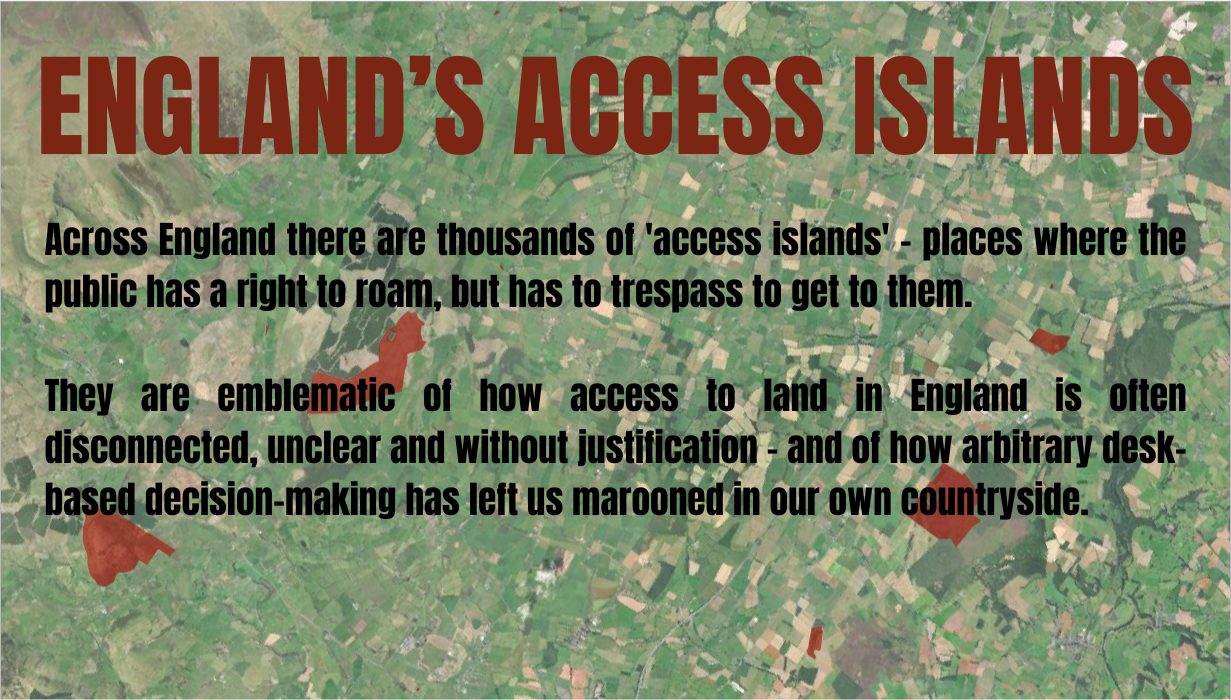

England's Access Islands

A process of costly desk-based mapping at the turn of the century created pockets of land to which the public technically have a legal right of access within, yet lack legal right of access to; in some cases requiring an act of trespass to exercise rights there. These are England's 'access islands'.

Across the country there are 2,500 access islands, in total covering 9,000 acres. They are emblematic of how access to land in England is often disconnected, unclear and without justification - and of how arbitrary desk-based decision-making has left us marooned in our own countryside.

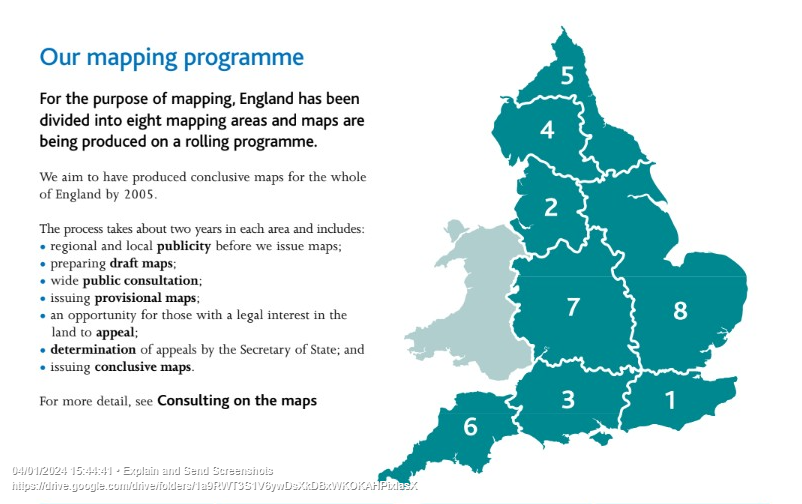

The Countryside and Rights of Way Act (2000) set in motion a long and costly process of attempting to map land the public would have open access upon - eventually ending with 8% of England's countryside made available across land defined as Mountain, Moor, Heath and Down.

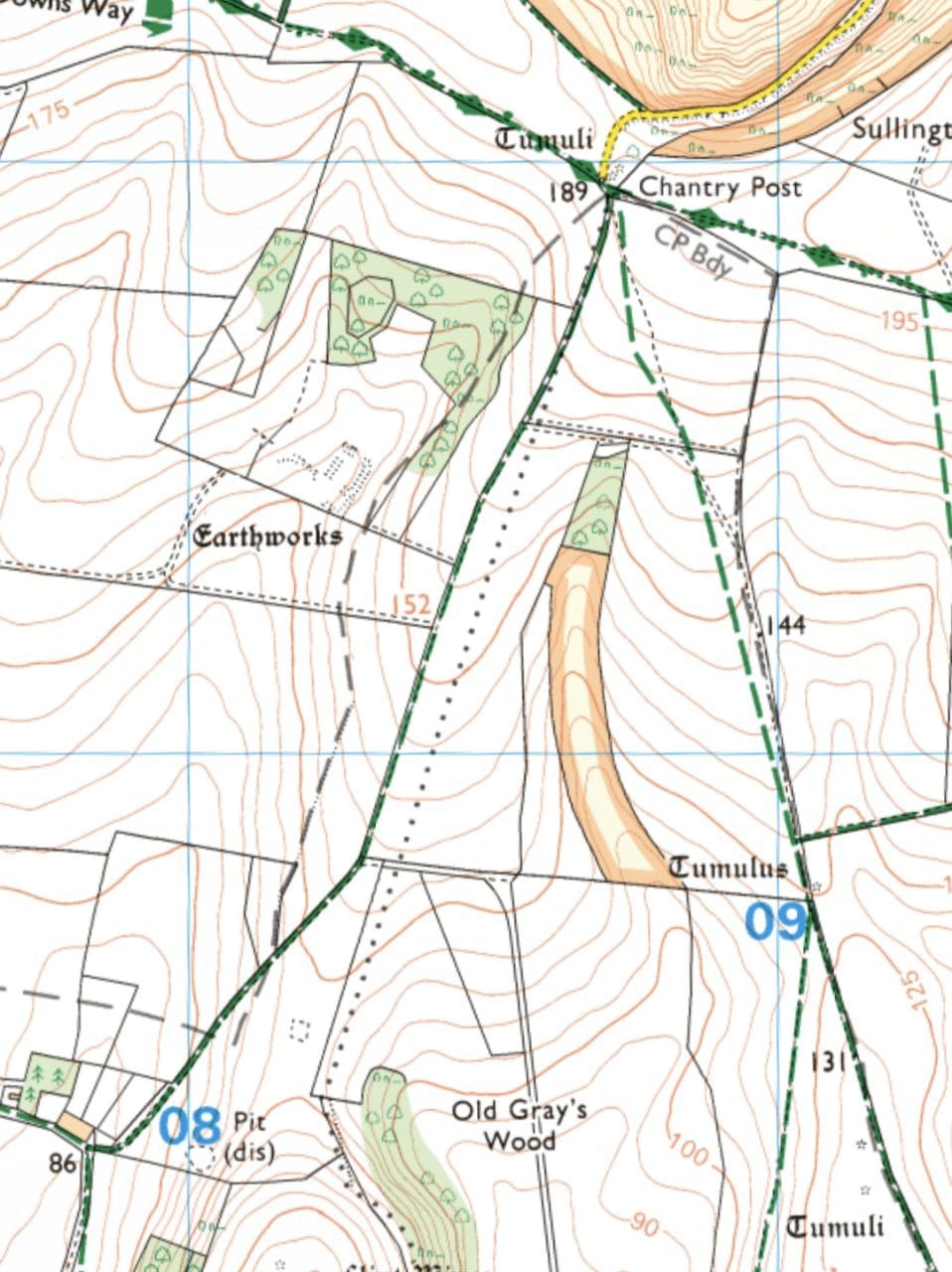

In it's Lessons Learnt report, the Countryside Agency stated that the project was one of the largest and most complex that Defra had ever had to deliver. England was divided into eight mapping regions, each of which was then subject to a convoluted back-and-forth process of drafting, consultation and appeal. In the majority of cases the land to be made accessible was never checked out on the ground, rather determined via desk-based assessment. To check out the viability of the approach would have required incalculable person-hours, yet not to do so has resulted in a disconnected patchwork of access. Additionally, the exclusion of improved or semi-improved grassland from CRoW made things even more complicated for the mapping authorities - in particular on ill-defined areas of downland where public access was heavily contested by land-owners at the appeal stage.

The Countryside Agency itself recognised the arbitrary nature of the Defra exercise at the time - stating: "Whilst this method of mapping has worked, in that the mapping work has been completed, it has resulted in a scattering of open country across southern England, and around the margins of the core areas of the northern uplands."

All of this bureaucracy has resulted in a set of odd and confusing relics in the form of access islands: a series of land parcels which technically we all have the right to be upon, but getting to them is another issue. Some of these locations include unconnected CRoW designated land which may have some (often very poor) access reliant on farm or forestry tracks or undesignated paths lacking legal protection for access. Getting to the land on which one has a right to be therefore relies upon an element of uncertainty and risk. Such access islands are Schrödingeresque: until a person actually attempts to get into one, it's unknown whether straightforward access will be possible, hindered or blocked entirely.

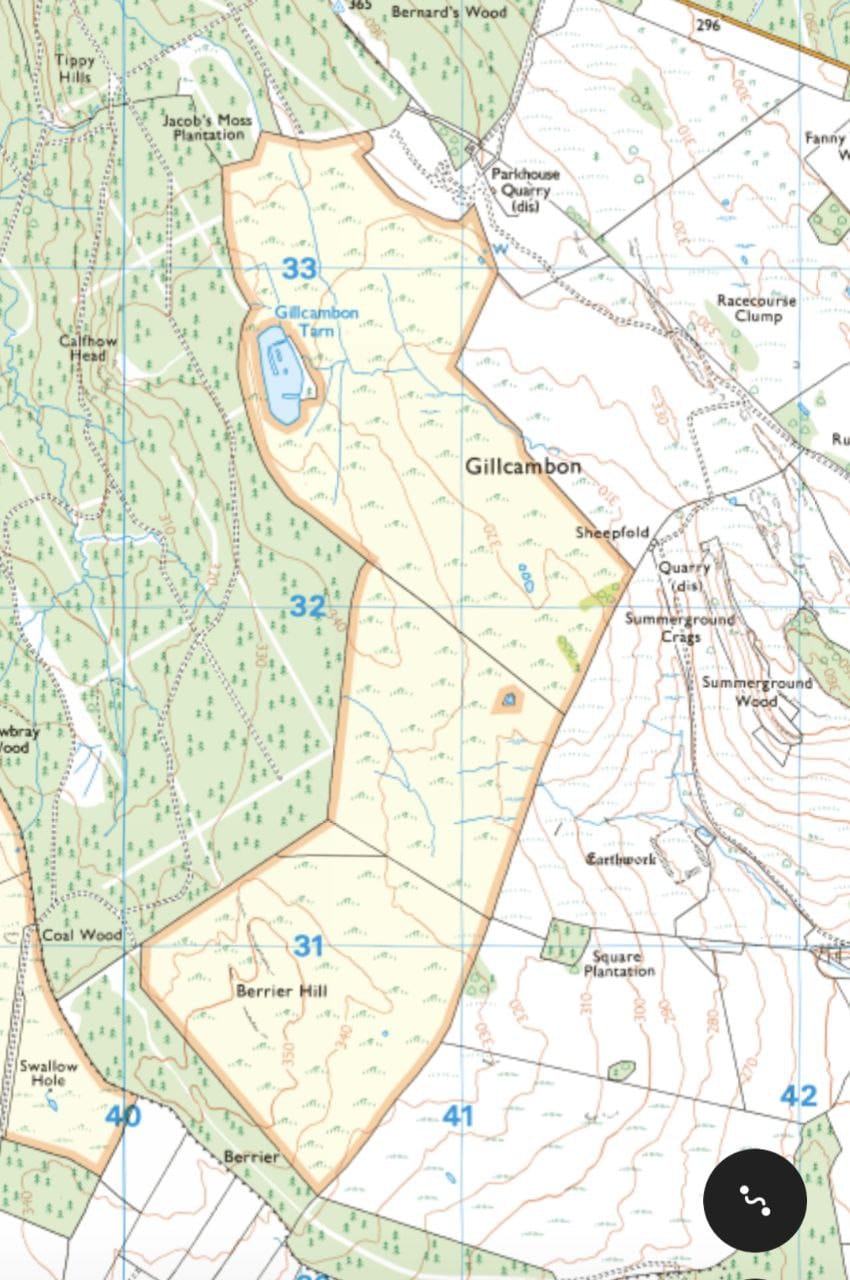

Also created by the haphazard mapping of CRoW were parcels of land to which access is absolutely impossible without trespass- but upon which the general public have every right to be. These range in size from the slender strips found amongst the chalky hills of the South Downs, to the entire fellside of Gillcambon in the Lake District (pictured above). Across England 2,500 islands cover 9,000 acres - an area of land equivalent in size to the city of York to which we've been sold a lie.

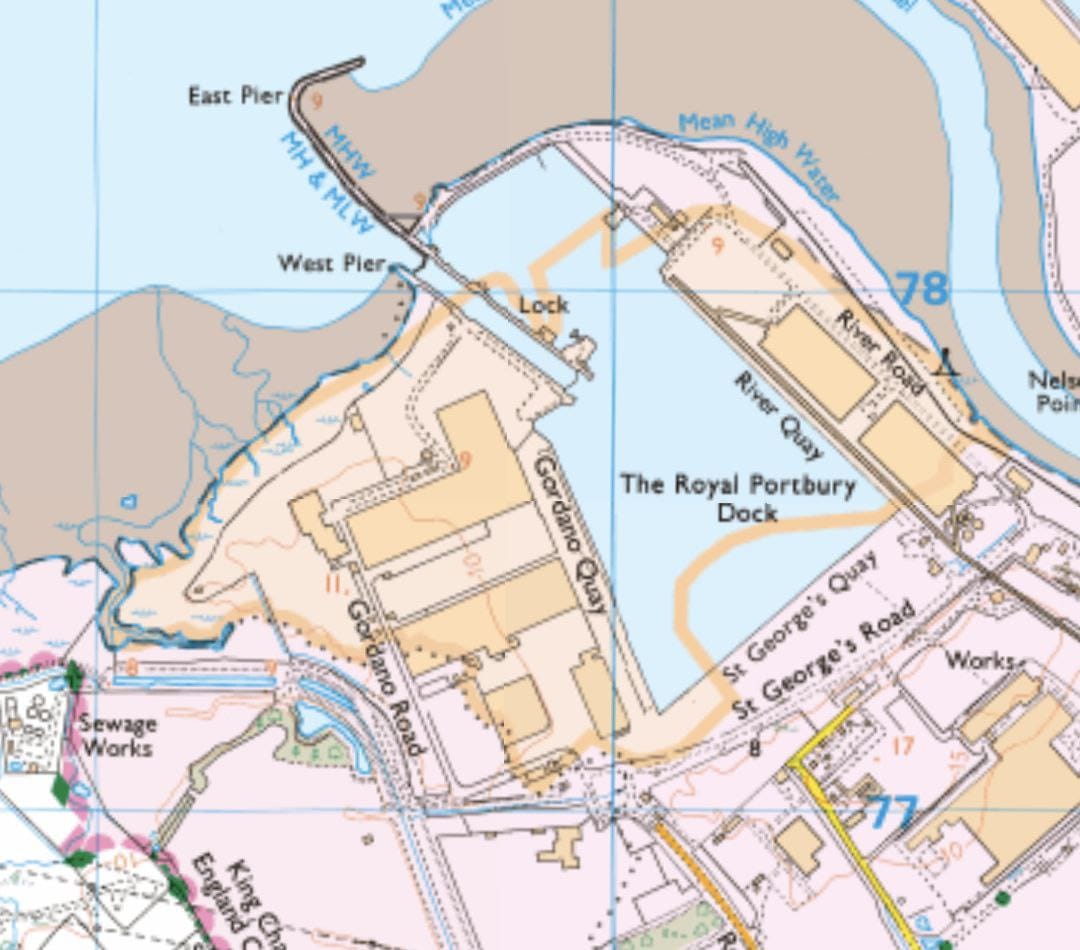

One of the most bizarre examples can be found at Royal Portbury Dock (thanks to Ian Walker for highlighting this), where - thanks to an historic common - the dock and surrounding area is designated as public access through section 15 of the CRoW Act, but no public right of way enables us to exercise this right (and as far as I know, uniquely for CRoW, this covers an area of water). This example was not picked up in our analysis (see explanation of methods below).

The brilliant vlogger Paul Whitewick visited an access island in one of his more recent videos here, and covers some background here; they are well worth watching for both interest and entertainment.

Determining public access based on landuse alone may work well in the uplands where most of our accessible land currently is, but the system utilised by the Countryside Agency and Defra in the early 2000's failed to deliver in the lowlands and downland where access is most severely lacking. The creation of access islands is illustrative of wider issues facing any attempt to extend public access beyond 8% of England: arbitrary desk-based approaches alone result in a lack of connectivity and clarity on the ground, and involve costly processes of consultation and appeal.

Far better, surely, would be to spend this time and money on determining areas which should - due to legitimate conservation and welfare concerns - be beyond a presumption of access, and to support responsible public access to the majority of the English countryside through education and resourcing. The CRoW process focused solely on where the public should be, and not how we should be when we're there.

Any meaningful attempt at extending countryside access would do well to learn from what has gone before - an expensive, lengthy and convoluted process lacking clarity and connectivity, no better illustrated than by the absurdity of England's access islands.

Data and methodology

- The Right to Roam campaign undertook this analysis by examining a number of official datasets. First, we built a GIS map of all Public Rights of Way (PROW) in England by combining all the maps published by English local authorities (downloadable at https://www.rowmaps.com/kmls/) into one big file. We then took Natural England’s GIS maps of CRoW Open Access Land and overlaid it with our PROW map to isolate areas of Access Land which are not connected to the PROW network. Next, we used the OS OpenRoad network layer to take out areas of Access Land accessible by road. We applied a buffer of 10m to take out Access Land that’s close to a PROW or a road, in case there are gates in etc. As a precautionary measure we also removed any potential access islands which fall within National Nature Reserves (NNR), Local Nature Reserves (LNR), National Trust sites and Forestry England estate land (freehold and leasehold), on the assumption that these would be accessible.

- We applied a 100m buffer from the coast, given the relative ease of access to coastal margins (and to eliminate anomalies in littoral zones).

- Access islands within urban extent have also been removed (although some urban access islands exist - such as the one in Royal Portbury Dock - we erred on the side of caution here).

- The resulting figure of around 2,500 access islands is, we believe, a very conservative one. We recognise that the methodology employed for this analysis has likely resulted in many access islands left unidentified by virtue of them being very close to PRoW or roads. We also recognise that some Forestry England land contains areas of potential access islands which have not been included in this research.